Bryan M. Ferguson: On Making It As an Indie Music Video Director and Surrealism in Horror

Hey shooters,

Some of you may have seen we’ve been running our SP Spotlight on Facebook and Instagram for SP members to share their successes and celebrate our community’s wins.

If you’ve ever wondered how to break into music video from a career founded on making films about self-amputation and belly-button fetishists, how to project on to a fog screen all using practical effects or how to approach big bands, read on about how Bryan approaches his brilliant work in surrealist horror and music.

This month, we’re focusing in on Bryan M. Ferguson, honing in on his work in surrealist horror and music video, ahead of his retrospective at LSFF on the 19th.

Going through your music videography, you’ve managed to maintain a really strong voice that makes this a distinctly “Bryan M Ferguson” video – to start, how did you get into directing music videos, did you already have the contacts in the music industry or did you hunt down the ones you wanted?

I had no contacts in the music industry whatsoever. I was working a 9-5 in a depressing office while making my weirdo short films in between and on weekends, then one day I get a random e-mail from Helen Marnie of Ladytron asking if I’d make a music video for their comeback album. It was just total luck after years of plugging away and hoping for someone to give a shit. It was one of the scariest things to do because I had no experience of making a music video at that time, so I went big on a really low budget because I didn’t know if I’d get another chance to do it.

Since then I’ve worked on many music videos, some through contacts that I’ve developed over the course of my career so far but I’ve also hunted down bands/artists either through their management or directly via social media and you’d be surprised how chancing your arm and forcing your work into the eyes of other people through twitter or instagram can really help get your foot further in the door. I’ve been very lucky to work with a lot of bands I really love.

You mentioned Ladytron scouted you? Any idea on how they found your work?

From what I know, someone who followed my work on instagram who was friends with the band and recommended me. I’m not sure what they saw in my early films (self-amputation, belly button fetishists and chlorine ingestion cults) that made them go, “yup, that’s the guy!”, but I really owe them so much for giving me that break and allowing me to start a career and make the work I’ve always thrived to make and experiment.

Obviously every shoot is going to be different, but what I noticed is that consistetly every music video you direct has an off-kilter unsettling feel to it. Do you typically get pitched the idea or get complete creative control?

I’ve been fortunate in that I’ve been given creative control – I’ve never really been given a brief. The majority of times I’ve been allowed the freedom to pitch my idea after listening to the track over and over.

Once the band like the pitch, you go shoot it then it becomes a bit more of a collaboration when you start to shape the video in the edit.

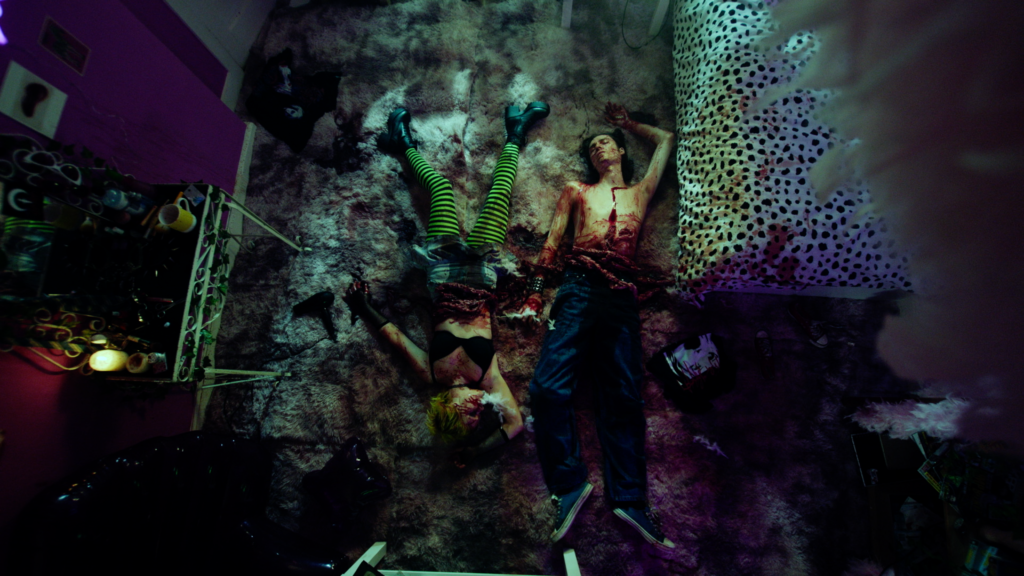

You recently dropped your music video for LOVE IS VIOLENCE with Alice Glass, to me, it really seemed to tap into the whole moral panic surrounding goth/punk subcultural scenes and their followers, was this just my reading of this or was it a conscious choice?

It wasn’t something I was consciously doing – with LOVE IS VIOLENCE I wanted to channel something that was a mix of a modern music video with the aesthetics of one from the early 00s (the mood setting introduction, the clip of Alice’s last single playing on the television) which is when the video is supposed to be set. The same era where I was a 15 year old goth, sitting bored, disaffected and flicking through music channels.

However now that you mention the moral panic, that was quite rife during that time because rock/nu metal/punk was kinda blowing up and dominating radios, so maybe it was something that was gestating subconsciously. That said however, I just wanted to make a really sick video were kids rip out their own guts.

In a lot of your music videos, I’ve noticed you use a lot of VCR shots which creates a great dissonance of including the icons behind the music and also outputting an independent narrative within them – I expect this is pretty challenging to do – what kind of equipment/setup do you use for this?

I love old tech – it just looks so much better. I have a disdain for modern technology in films, it just looks so boring. To capture a lot of the VCR imagery I try to avoid composites of TVs that are done in post and have the images on the televisions on the day of shooting.

I actually sometimes use an old CCTV camera that’s hooked up to it’s own monitor that I bought from eBay, it gives a really great texture to the images. For principal photography we usually shoot with a Blackmagic Ursa mini pro G2 to capture the CRT screens without flicker.

I’ve got to ask, the Fair Game video – how on earth did you get that smoke projection to look like that? I assumed it was VFX until I watched it back.

Yeah, a lot of people initially think it was VFX but I’m kinda old fashioned and push to do everything practically (mainly because I have no knowledge of VFX or how they work). We got in touch with a guy who owned a fog screen, which is sort of like a wall of fog made with water vapour then we’d project Alice’s face from behind. For her face to appear in mid-air, we’d use this huge industrial fog machine pipe that when you fogged up the projection beam Alice’s face would materialise in thin air like a ghost, it was insane to see in person.

You seem to have made a real name for yourself within darkwave music, was this intentional or have you found yourself just naturally gravitating towards this?

Darkwave is the music I tend to listen to the most, so it’s just a natural gravitation, it also helps that my visual style melds well with that sort of sound, it’s also those tends to be the bands that I hunt down to work with. There’s something really cinematic about the sound too.

As a big horror fan, a lot of your work really impressed me and was distinguishably different in how it leaves the viewers with brainworms about the reality of these narratives being possible – where do you find inspiration for these sorts of things?

I honestly don’t know, my brain is just wired a certain way. Like everyone else, I find inspiration comes from every possible source imaginable and my brain tends to sort of distort whatever mundane thought or interaction I’ve had into something that’s a little bit fucked up. I love perverting the perception of something that’s completely normal. I have a million ideas that twist the ideas of everything from hand dryers to cotton buds. Unfortunately these are the ideas that no one really wants to commission and you get asked if you’re nuts a lot.

Film festival fainting – have you ever found the backlash from being directorially known for being so gory loses you opportunities? How did you go about finding platforms like Short Acts which would be

willing to take the gamble with their audience?

Absolutely – you get pigeonholed fairly quickly which is crazy because people have this idea that my work is “gory” but the only time in my 10+ year career that I’ve explicitly shown any gore was literally this year with Alice Glass’ LOVE IS VIOLENCE. I come from a place where the less you show the better. The fainting at the screening of FLAMINGO was purely gaps being filled in by the viewer’s imagination. In the film there’s literally a red censor bar obscuring anything nasty from view because nothing I can show the viewer will be half as awful as what their own mind will conjure up.

But alas I still miss out on opportunities purely because I make work that can sometimes make people feel uncomfortable. On the plus side, I get work a lot of work for that very reason and it means a client, production company or band know what they’re in for and I can have my bloody fingerprints all over what I make without any real interference.

Getting SATANIC PANIC ’87 made through Channel 4’s Random Acts was a 3 year process, pitching, convincing, meeting with and change of commissioning heads were all factors but I eventually wore them

down and they took a chance on me to make something pretty manic and were completely hands off and encouraging. It was great to see a platform that big allow me to explore granny murder and possessed arm chairs that become portals to hell.

Red Room – as far as I’m aware this was your first time adapting a book (Bitterhall) – how did this differ from your other shorts where you were also the writer behind your work?

When I was asked to adapt Bitterhall I jumped at the chance because it’s important to me as a filmmaker to constantly challenge myself and experiment as much as I can. I had never adapted anything before, the idea in the past was quite daunting but I found it really exciting to take someone’s ideas and sculpt them into something that was partially mine and creating a sort of mutant child from the minds of two people that work in different fields.

It was tough because the book is quite dense with a roshomonesque three point perspective narrative, so to condense that into a short that was initially commissioned as a 5 minute film was nearly impossible, it really had to be 15 minutes to get some semblance of what the book is conveying. So I basically dogeared the book and highlighted everything that excited me and then started to construct my own companion narrative into a more condensed story that leaned heavily on atmosphere.

Also on Red Room, it felt distinctly less visceral/manical than your previous work, really playing up on psychological/paranormal horror opposed to your other short work which has really played into the

fears that this could, quite literally, be real – is this something you see yourself tapping into more?

Definitely something I want to explore more, I’m very much two filmmakers trapped inside one suit of flesh. One is this complete live wire who wants to rip through set and make the most crazy fucking thing I can and the other side is more contemplative, psychologically fucked up. This can be seen in Flamingo, albeit a more visceral film but still taps into a subculture that exists with fears that are real.

With Red Room, I really wanted to test myself and show restraint. It was a challenge to hold back and explore different avenues. To show a side of me that can really play with stripped back paranoid camera set ups with atmosphere and performances over manic energy. I think a lot of people will be surprised by my first feature which I’m currently developing with Screen Scotland/BFI.

What’s really stuck out to me with a lot of your work, is that you’ve managed to evade the typical pitfall of horror where people use scores to build tension, when really it just makes it guesswork to when the climax actually will be – do you work on your own sound design? Is sound design something you pre-empt or mostly complete within the edit process?

I’ve always edited my own stuff which means over the years doing my own sound design has become part of the process. Editing is my favourite part of the entire process and I love ripping out all of the sound and creating it all from scratch, building the soundscape of the world you’re building. Some sound cues are scripted or ideas I have when writing and other times it’s something that organically happens when cutting. I always want to transgress the filmmaking formula.

If you’re interested in being spotlighted, why not submit your short?

Similarly, if you’re interested in hearing more from Bryan – grab your tickets for his retrospective at LSFF ‘Irregular Atrocities’ on the 19th of March.

To connect with shooters like Bryan and other great filmmakers – join the SP community today!